“… We heard on passing into Belfast through a most wretched suburb that most disgusting of all noises worse than the Bag Pipe, the laugh of a Monkey, the chatter of women solus the scream of a Macaw – I mean the sound of the Shuttle – What a tremendous difficulty is the improvement of the condition of such people – I cannot conceive how a mind ‘with child’ of Philanthropy could gra[s]p at possibility – with me it is absolute despair.”

[Letter 5 to Tom Keats, 3-9 July, 1818. ‘John Keats Selected Letters’, ed. John Barnard, Penguin, 2014, p. 189]. ‘Walking North With Keats’, p. 168.].

I stumbled on these words again, recently, re-reading one of my favourite books, “Walking North with Keats’, Carol Kyros Walker, Yale University Press, 1992.

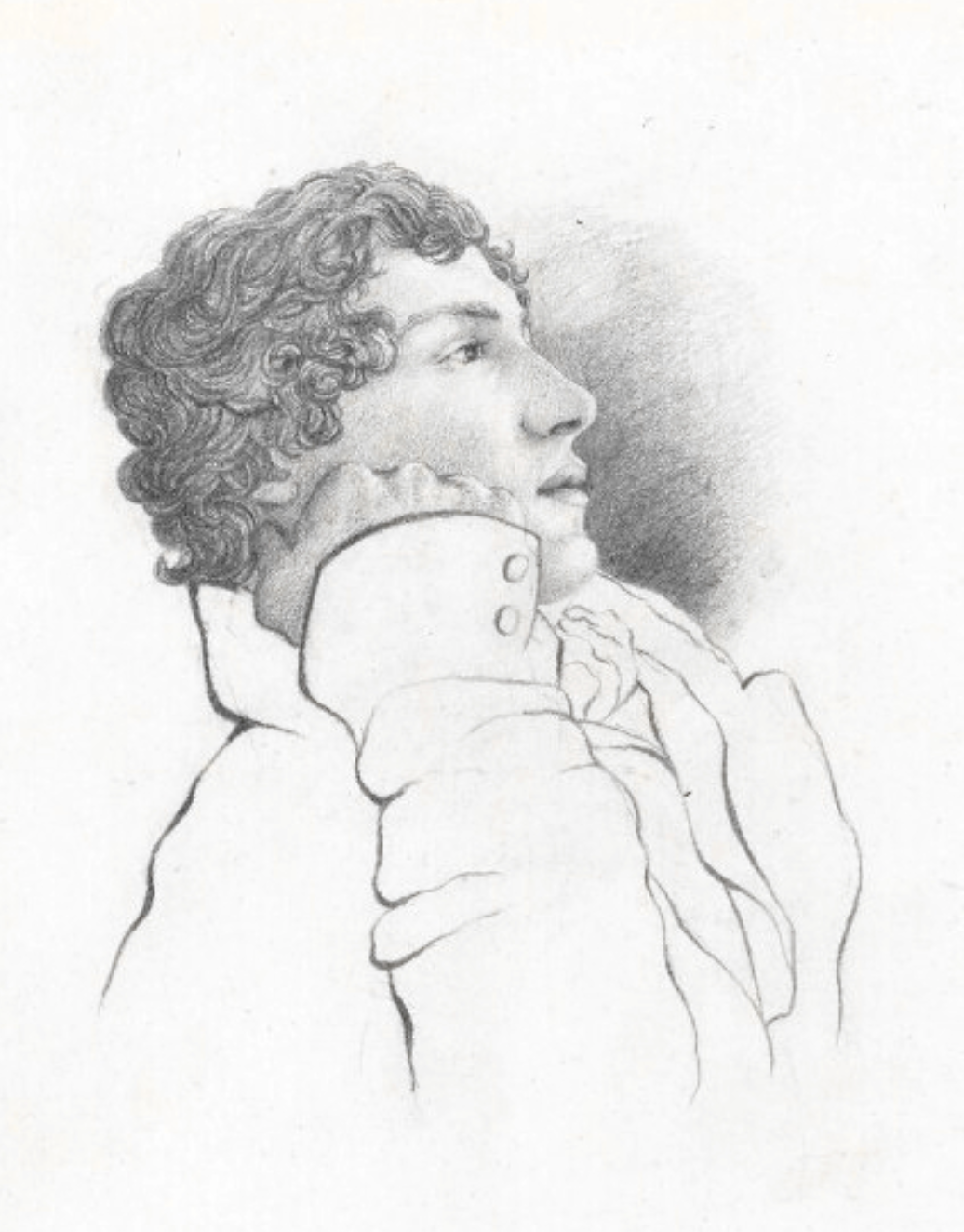

I’ve had a lifelong obsession with John Keats, and yet not been able to weave him into my work, until now. I had somehow forgotten or missed these words in Keats’ letter to his brother Tom, from the summer of 1818 when he made his walking tour of Westmorland, Scotland and Ireland, writing home to Tom as he lay dying at Well Walk, Edmonton. How did I forget this? As soon as I saw this paragraph, I knew I’d have to write about it.

Keats’ published writing career spanned only the 4 years between Waterloo and Peterloo. A time of economic privation due to the Napoleonic Wars and huge working class unrest – the Luddites had been hung like crows on a fence only six years before Keats went on his walking tour. There is more to unpack in his brief encounter with the Belfast weavers, than we might assume.

So come with me, Gentle Reader, for a stroll where we will unpack Keats’ brief but startling encounter with the Belfast cotton industry. There is more to unpack than you’d imagine.

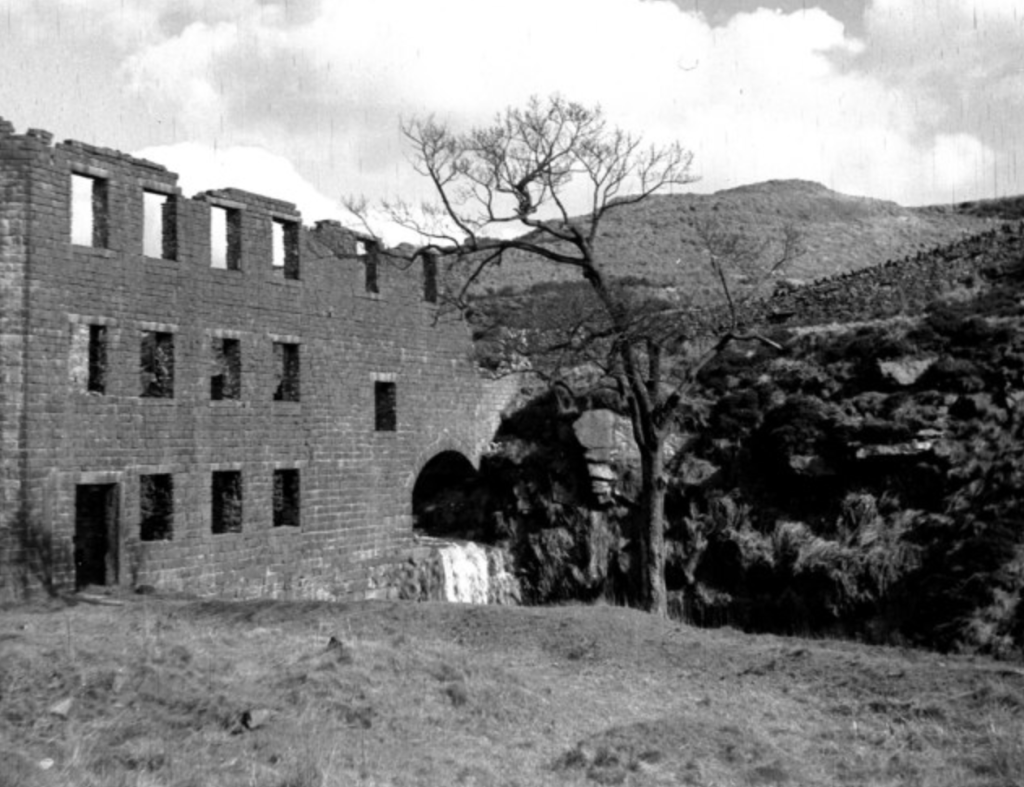

When we think of Belfast textiles, we think of linen. But it wasn’t always so. From the 1770s, to the 1830s, the North-Eastern part of Ireland was pre-eminent in cotton production. And this was what Keats will have seen on his (brief) sojourn in Ireland. The industry that offended Keats’ ears – and politics – seem to have had had a rapid decline after the depression of 1825, and the removal of trade protections, just 4 years after Keats’ death. In its heyday, the Irish trade exported in large quantities to America and South America and produced some of the finest cotton thread in the world.

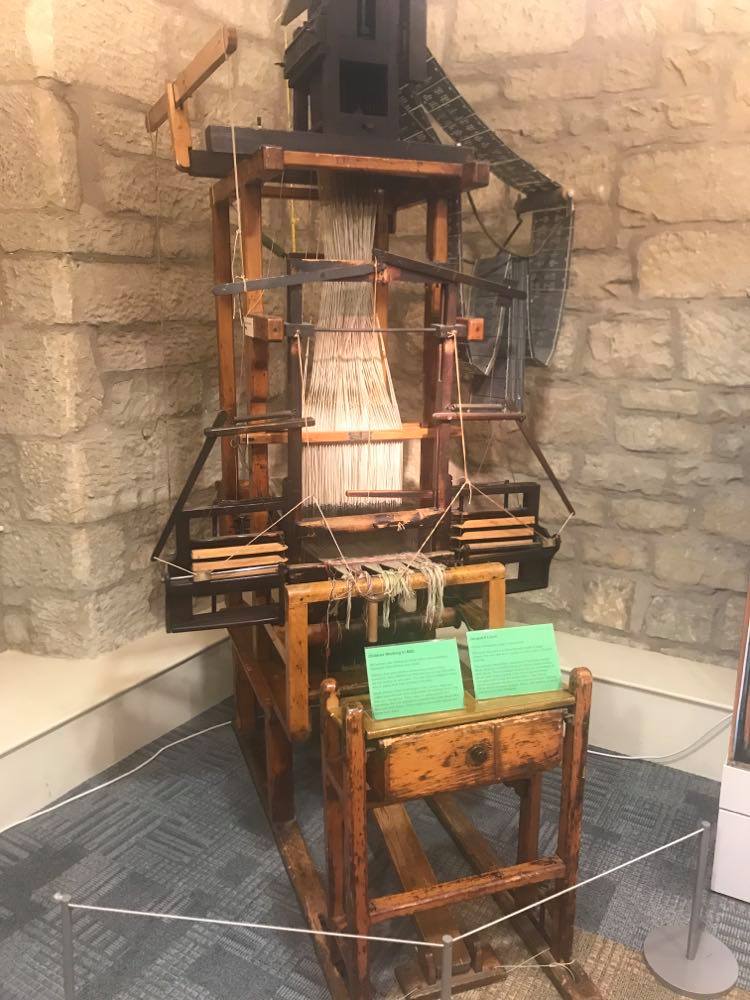

In the late eighteenth century, textile production shifted from cottages to manufactories. One woman spinning flax or wool on a simple spinning wheel to make a single cop (cone) of yarn, at home, developed into vast manufactories filled with unskilled workers – usually children, in the case of spinning machines – supervising rows of water, then steam powered machines, each spinning jenny having 72 heads. Child labour was cheaper than adult labour. So children as young as six, were used to work 16 hour days in factories. (For more info on child labour in the 19th century, see Their Darkest Materials). In fact by the time Keats encountered the streets in the shadow of the dark satanic mills, there was already a parliamentary enquiry underway into working conditions for children in cotton mills. Specifically cotton mills – they were thought to be more “barbaric” than wool, flax or hemp manufactories.

Sometimes, we forget that romanticism was born in the same moment as industrialisation and in many ways was a kneejerk reaction to the burgeoning world of machines and their dehumanising effect on people and despoilation of the natural world. During Keats’ and Brown’s brief stay in Ireland, Romance was headed off at the pass by Industry and Romance beat a hasty retreat.

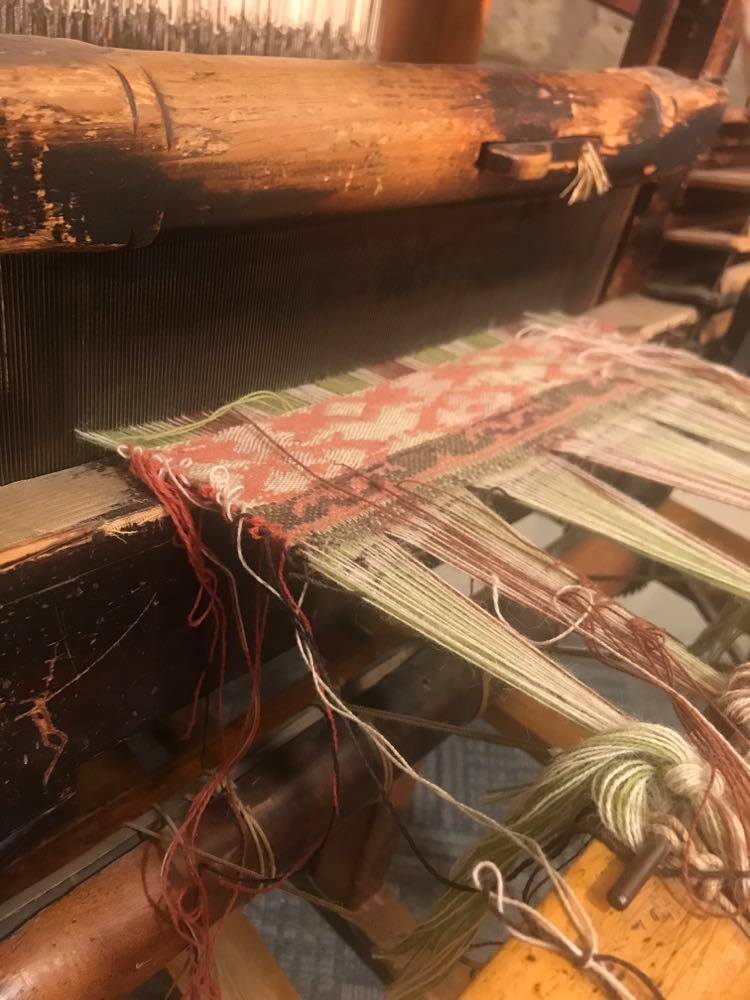

Decades later, in the 1880s, Wordsworth’s fan Albert Fleming revived the linen industry in Westmorland and Cumberland. He wrote of finding an elderly lady in his village – she would have been a little younger than Keats, had he lived – who remembered how to use a spinning wheel. Inspired by Wordsworth’s encomiums for the art of hand-spinning, Fleming set about reconstructing the craft:

“ ‘In mother’s day,’ said my old friend, ‘every woman spun but when t’wheels died out the gude times went too; m’appen they’d come back if t’wheels did.’ Then and there I determined that the wheels should come back. ‘The venerable art torn from the poor’, should, God helping us, be given back to them.”

[‘Revival of Hand Spinning and Weaving in Westmoreland’, Albert Fleming, The Century, v. 37, 1888].

Fleming’s revival of the Westmorland linen industry was essentially a death throe of the romantic movement that started with Keats walking past those Belfast mills’ weaving sheds.

The dissonant sound of the shuttle would suggest the Belfast weavers were using power looms and by this date, steam power was superceding water.

By the late 18thC, linen – which had been ubiquitous for shirts and underwear for centuries – was making way for the new, more fashionable, cotton. New inventions like Eli Whitney’s Cotton Gin led to an explosion in the slave trade – and new tech plus slaves in the New World led to the sudden cheapness of cotton as a raw material, in the Old.

As an area of linen production excellence, Belfast was well placed to be the centre of a new cotton industry.

Thomas McCabe and Robert Joy are credited with introducing cotton to Ireland, as a textile product. They commissioned the first spinning jenny in Belfast. Cotton spinning beginning in earnest in the city around 1777 with spinning jennies and carding machines put to use. Weaving and dyeing followed. Designs were often printed on the finished cotton fabric in Dublin or Manchester. Soon, Belfast wasn’t just carding and spinning cotton but exporting finished bales of cloth.

Cotton production in Belfast started as a philanthropic affair but quickly morphed into industry and enterprise.

Robert Joy introduced the industry “by a desire to render service to the lower orders of the working poor, particularly linen spinners and weavers…” Thomas McCabe wanted to establish cotton spinning as “fit and profitable employment for children in the Belfast Poor House” and initially several children were taught to spin cotton on a wheel but McCabe soon decided that machinery would be preferable. Nicholas Grimshaw, an English cotton and linen spinner who had lived in Ireland for a few years, supervised the making of the first spinning machine in Ireland – a spinning jenny made in Belfast. A Scottish spinner was brought over to teach the children how to work the machine (unskilled, as the machine did the work, children just had to keep the spindles going). McCabe and Joy, finding the poor house reluctant to fully fund the venture, went into business, promptly engaging in a bit of industrial espionage, sending a skilled mechanic to England to get experience of the latest spinning and carding machines there, in order to return to Belfast to build replicas of them. The result was a new and improved carding machine and a spinning jenny with 72 spinning heads.

The new machine could spin 14 times the length of yarn of a competent handspinner, in one week and the carding machine could card 20lbs of cotton per day, as opposed to the paltry 1lb per day achieved manually by hand cards alone. In 1784, the first water mill powering spinning frames, in Ireland, was introduced and by 1800, 13,500 workers were working in the Belfast cotton industry.

[More information in ‘Cotton Manufacture of Belfast’. The Belfast Monthly Magazine, vol. 3, no. 16, 1809, pp. 342–344. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/30073610. Accessed 23 July 2021].

From these small beginnings, a prosperous cotton industry grew with many cotton mills centred in and around the city.

By the 1820s, mills were largely moving on from water power to steam power and the jarring sound that irritated Keats is likely to have been steam powered looms.

The noise in Lancashire cotton factories was so loud, that workers developed their own kind of sign language to make themselves understood. Known as “mee-mawing”, it was recorded for posterity in Les Dawson’s 1970s’ Cissie and Ada act, where Les and Roy Barraclough played two middle aged women who mimed all the scatalogical content of their conversations – this came directly from Dawson’s observation of women from the Lancashire mills.

It’s maybe worth pausing here to mention Keats’ links with Lancashire; the epicentre of the Industrial Age’s origins.

When his parents died, Keats was put in the care of a Lancashirewoman. His maternal grandmother, Alice Jennings hailed from Colne, Lancashire, born c. 1736. She had only been in London several years when she married Keats’ grandfather, John Jennings, so it is likely that even when Keats knew her as an elderly lady, she still spoke Lancashire dialect. She came to London around 1770. When first wed, in 1774, Alice lived with John Jennings at his inn, ‘The Swan and Hoop’, 24 Pavement, Moorgate. It was said the Jennings family were Non-Conformists . Although the Jennings had an Anglican wedding – family members were to be buried at Bunhill Fields, originally “the Dissenters’ burial grounds”.

According to records on Ancestry.com, one Alice Whaley, daughter of John Whaley, was baptised November 1st, 1736, in Colne. I can’t be certain this is her, but it is possible. I’ll continue to search laterally and hopefully will find Alice’s father’s profession but if it was textile related, I wouldn’t be surprised. Colne had its own cotton mills by Keats’ day many with their origins in the 18th century or earlier, when the industry would have been woollen cloth production. We know this as many mills had their origins as fulling mills – a process only needed for wool, not flax or cotton.

By the time Alice moved to London, the Industrial Revolution in Lancashire was underway but like many Lancashire women of an earlier generation, she may well have known how to hand spin wool and linen, if not cotton. We shouldn’t overlook Keats’ Lancastrian roots and it may be that Alice originally came to London to escape working in the new cotton mills. This may also have prejudiced John against the clattering power-looms.

“…Keats knew that to ‘literary fashionables’ his name was no better than that of a Dorset weaver boy – as vulgar as the poor citizens so cruelly trampled at Manchester…” [‘John Keats’ – A New Life, Nicholas Roe, Yale University Press, 2012, p. 342].

When Keats walked into Belfast, we encounter a classic clash between romanticism and industrialisation. He was not expressing disgust for the weaver or the working classes. But for their exploitation. Keats was progressive and radical by nature. There was a lot he’d find challenging, coming face to face with the realities of early industrialisation.

A year after his walking tour, Keats may have become aware of Samuel Bamford, “the weaver poet”, a versifying Lancashire weaver. Bamford was a politically radical advocate of the working classes, who sometimes wrote his poems in a dialect that for Keats would have recalled his Lancashire grandmother. A year after Keats’ walking tour, Bamford was charged with treason after the Peterloo Massacre in 1819 and got a year in prison for inciting a riot (despite evidence in court suggesting he did no such thing). In that same year, Bamford published a collection of poems, ‘The Weaver Boy’. Like Leigh Hunt, he continued to publish, even in prison.

The Acts of Union had united the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland in 1800. In the year after Keats’ walking tour, at Westminster, the government would pass the 1819 Cotton Mills and Factories Act which was the first piece of legislation trying to regulate children’s working hours. A Lords’ Committee heard evidence from Lancashire cotton mills, where, according to Hansard, Sir Robert Peel stated that over 20,000 people worked in the cotton industry. This Act was deeply flawed. It only applied to cotton mills not linen or woolen/worsted and millowners were often the magistrates so not about to enforce the law if it cut their profit margins. The Act prohibited children under 9 working. Hours were restricted to 12 a day for the under 16s. But this meant that even with the Act observed, a ten year old worked from six am to six pm.

Keats had every reason to be contemptuous of the cotton mills. Part and parcel with this, his radical nature branded him with reviewers such as Blackwood Magazine’s John Lockhart, as “the enemy within” – Bonaparte had been defeated but radicals like Keats represented the “reds under the bed” to the Tory mind. And there was a lot in the textile industries to disturb those of a more radical sensibility.

Lancashire had strong links with the Irish cotton trade. The Irish millowners seem to have been in close communication with similar manufacturers in Manchester and Glasgow, and Scottish, English and Irish cotton mills would seek out eachothers’ opinions of the latest advances in the technology. Hand looms continued to be used in Ireland, England, Scotland and Wales, as well as power looms but in the case of the Belfast cotton industry, as it had been, almost from its inception, an industry founded on latest technology, I suspect the handlooms in Ireland will have not been common in the cotton industry, because the Belfast cotton industry was technology-led from its beginning. There are records extant of Midlands, Lancashire and Scottish machinemakers extending credit to Belfast cotton mills throughout the period Belfast cotton held sway, suggesting the technology was constantly being upgraded.

In Belfast, it is thought that cotton was auctioned on the quays, directly from the American ships. Imported cotton came from America and the Caribbean – and both would be the product of slave-labour. Keats did not write expressly about slavery – and few biographers until Andrew Motion have seen him as a truly political poet – but in view of the general, radical tenor of his political opinions, we can probably safely assume he was not in favour of it. We can be certain his horror at the sound of the shuttle was partly caused by his sympathy with the oppression faced by the Irish cotton weavers; but can only imagine that it is likely his mind also strayed to the vile reality of slavery that made this cotton suddenly more plentiful and cheaper.

[More info here: Geary, Frank. ‘The Belfast Cotton Industry Revisited’. Irish Historical Studies, vol. 26, no. 103, 1989, pp. 250–267. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/30008599. Accessed 23 July 2021.

Keats and his friend and travelling companion, Charles Armitage Brown, decided not to linger in Ireland: “We stopped very little in Ireland… living in Ireland [is] thrice the expence [sic] of Scotland”. They had also found the landscape between Donaghdee and Belfast uninspiring. So they turned round at Belfast and returned to Donaghdee, to get the ferry back to Scotland.

Keats continued:

“…At a miserable house of entertainment half way between Donaghdee and Bellfast [sic] were two men sitting at Whiskey one a Laborer and the other I took to be a drunken Weaver – the Laborer took me for a Frenchman and the other hinted at Bounty Money saying he was ready to take it…” [189]

It’s apparent the weaver thought Keats was from an English pressgang. The fact he was eager to be pressganged, tells us a lot about the grim nature of working in a cotton manufactory.

In the same letter to Tom, Keats famously said: “…We live in a barbarbous age…” There was a stark contrast between the romantic abbey ruins, and Robbie Burns’ cottage, and the “romantic” landscapes Keats and Brown were seeking out on their walking tour, and the noisy, bustling cotton mills of Belfast. Romantic poets were living in the Anthropocene age – characterised by humanity’s impact on the environment. And they were amongst the first people to realise this and react to it. To put the jarring encounter with Belfast industry in context, Keats had just published ‘Endymion’ – a sort of pastoral idyll, the poem with the famous opening line:

“A thing of beauty is a joy forever…”

He may have been aware of the then ongoing parliamentary commission looking into child labour and working conditions in cotton mills. He was likely also aware of William Blake’s “dark satanic mills” of fifteen years earlier – which probably referred to the flour mills in Southwark, powered by Boulton and Watt engines (there are extant records from Belfast cotton mills, recording the purchase of Boulton and Watt machinery – this will have powered the looms). When Keats wrote to Tom:

“… I cannot conceive how a mind ‘with child’ of Philanthropy could gra[s]p at possibility – with me it is absolute despair…”

He was expressing anguish about the effects of industrialisation and how it might be impossible to reverse – a catastrophe for the environment and the human beings who worked in it. Philanthropy had been grappling with industry since the 1770s (see https://theknittinggenie.com/2015/06/09/inside-the-wool-spinning-mistresss-closet/, where I discuss the Unitarian Catharine Cappe’s attempts to help York child prostitutes and child workers in a hemp manufactory, in the 1770s and 80s). Philanthropy was still grappling in 1818.

Keats’ reaction to the weaver he met, could be taken on face level as a sort of snobbish alarm of the effete “dandy” poet encountering working class men. It is not like Wordsworth’s “romantic” reaction to leech gatherers and beggars (both, arguably, more rural and picturesque), who became grist for the mill that transformed the indigent into the poetry of ‘Lyrical Ballads’. I don’t read Keats’ reaction to the cotton industry that way. To understand Keats’ mindset, we have to understand a little more about him.

Keats came from a middle class background, unlike the distinctly aristocratic Shelley and Byron. He had completed his formal training as a surgeon (not apothecary), when he decided to take the plunge and be a poet, not a medic.

Keats had attended the liberal and progressive Clarke’s School, in Enfield. Keats first read Leigh Hunt’s Examiner, there. It was where Keats’ radical spirit was forged – as a boy, long before he moved in radical circles or published in its pages.

From the start, Keats’ literary friends were a radical circle, most notably, Leigh Hunt, editor of The Examiner, friend of Shelley, and recently, inmate for two years for supposed sedition. “… For the reviewers Keats was guilty by association, and the damning association was with Hunt…” [Cronin, Richard. “Keats and the Politics of Cockney Style.” Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900, vol. 36, no. 4, 1996, pp. 785–806. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/450976. Accessed 23 July 2021].

Tory reviewers made brutal attacks on Keats, during his lifetime. The most vicious, came from John Gibson Lockhart. It was published in Edinburgh the very month Keats was walking North and came out in London only days after his return home.

During the summer walking tour, Keats already had the Tory reviewers’ target pinned on his back. And even as he spoke with the weaver and labourer, he was aware that he’d been associated with the Cockney School, and was seen as “lesser” by many in the literary establishment. Lockhart was about to belittle Keats as “plebeian” in his most vituperative, malevolent article mocking him for being “plebeian”. Lockhart snobbishly put Keats in the class of governesses and footmen who were would-be writers.

Keats’ latest published poem,’ Endymion’, was dismissed as “drivelling idiocy” – words so strong, you can’t help thinking of today’s far-right shock-jocks, out to get a reaction for attention and follows – and in Lockhart’s case, sales of the then-flagging ‘Blackwood’s’. Whilst Keats was touring, Lockhart had got the poet’s life story from one of Keats’ friends, who was defending him, and fatally, gave enough backstory for Lockhart to weaponise:

“… it is a better and a wiser thing to be a starved apothecary than a starved poet; so back to the shop, Mr John.”

Keats – dismissed as a mere “apothecary” and “plebeian” by the Oxford-educated elite who could stomach their contemporaries Byron and Shelley, and the now safely staid and Tory Wordsworth, but had no time for this “Cockney” upstart. Deep down, in his reaction to the Belfast weaver and encounter with the city’s cotton mills, I suspect there was also shame and anger at his Blackwood’s disdain for the “Cockney School”. His brief encounter with industry foreshadowed the dark, satanic times ahead as the reviewers’ perception of his social class, hinted at in previous reviews, was about to take centrestage.

At the end of his tour, Keats decided to sail home without Brown, on a small vessel called The George, which as well as passengers carried cargo, such as the Edinburgh journals, down South.

It’s likely that amongst its holds were copies of the Blackwood’s magazine, with Lockhart’s latest excoriating piece, responding to ‘Endymion’. Keats wouldn’t have been aware of it, yet. But returning from his walking tour, he was literally sitting on top of the powder keg that was about to blow his literary life apart. His life would never be the same again.

Cronin, Richard. “Keats and the Politics of Cockney Style.” Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900, vol. 36, no. 4, 1996, pp. 785–806. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/450976. Accessed 23 July 2021

Geary, Frank. ‘The Belfast Cotton Industry Revisited’. Irish Historical Studies, vol. 26, no. 103, 1989, pp. 250–267. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/30008599. Accessed 23 July 2021

Gittings, Robert, ‘John Keats’, Little Brown & Co, 1968

Hansard, Debate, 19th February 1818, Vol 37 cc.559-66

Keats, John, ‘John Keats Selected Letters’, Penguin, Ed. Barnard, John, 2014

Kyros Walker, Carol,, Walking North with Keats’, Yale University Press, 1992

Motion, Andrew ‘Keats’, Faber & Faber, 2018

Roe Nicholas, ‘John Keats – A New Life’, Yale University Press, 2012